|

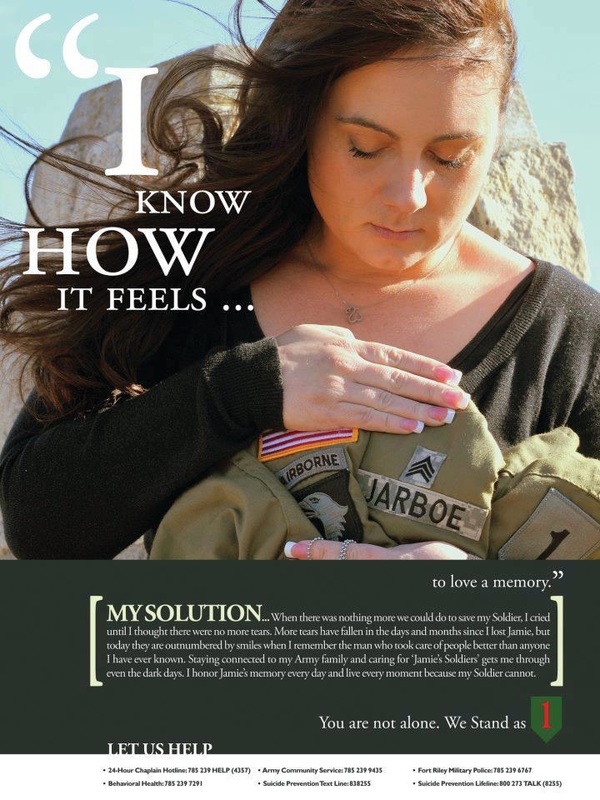

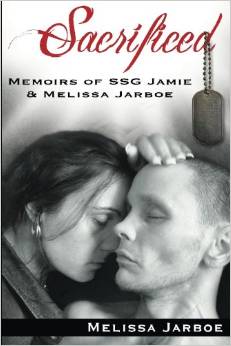

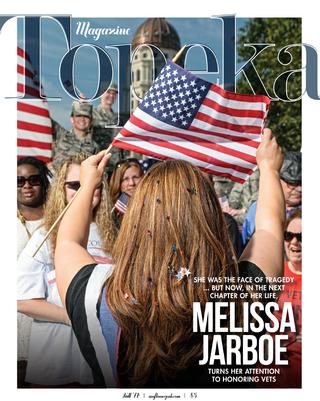

By SHERMAN SMITH - Associated Press - Monday, November 23, 2015 TOPEKA, Kan. (AP) - If the Military Veteran Project succeeds at improving brain injury treatment and other goals, Melissa Jarboe won’t be running the organization she founded.As MVP membership swelled the past three years, Jarboe has struggled with personal constraints, narrowed the organization’s focus and rejected donations. “I’ve learned to understand I’m personally attached to MVP,” Jarboe said. “I don’t want us to grow. I don’t know how much I can handle as a volunteer, and I don’t know how much my volunteers can handle. So in the next year our goal is to hire somebody that can.” The decision is a calculated move for an organization founded to fulfill her husband’s dying wish to help fellow service members. In an interview at her Topeka home, Jarboe talked about the exhaustion of running MVP, pressure to relocate to the nation’s capital, and the ways Topeka has saved and hurt her efforts, The Topeka Capital-Journal reported (http://bit.ly/1X98RPV). “We won’t grow too fast here,” Jarboe said. “Not everybody will let us.” An MVP board respectful of Jarboe will have to find a new leader while pressing for a refined identity and setting its sights on a partnership it hopes will reduce veteran suicides. Jarboe will remain the public face of the organization. “I think you learn that you are not the person suffering, so you’re irrelevant at that point,” Jarboe said. “I know I can wake up each day and enjoy the freedoms. I can breathe. I can walk. I can talk. I can organize. But I know there are men and women out there suffering who fought for the freedoms I use daily who don’t have those freedoms when they come home to American soil. “That keeps me grounded. So while something so tragic happened to me, it really doesn’t matter. I still have my freedoms and my life. I think you put that in perspective, right? Don’t need to be selfish about it. “I might get some backlash on that comment.” Jamie Jarboe died a year after suffering wounds from a sniper’s bullet in Afghanistan. In a 2012 interview with The Topeka Capital-Journal, his widow blamed “the negligence of the military hospitals” for his death. “When I first created the Jamie Jarboe Foundation, I did it because I needed something to help me carry Jamie’s legacy on,” Melissa Jarboe said last week. “He left me with the last wish to take care of his service members, and I had no idea what that meant. That was the hardest part. I had to figure that out.” She spent a year traveling the nation, “gone every other week,” visiting military bases and answering calls of distress. She found herself caring for active duty soldiers, military spouses, widows, wounded warriors and veterans. “They were struggling in one way or another,” Jarboe said, “and for some reason, I always knew how to fix it and get them the help they were struggling with for a good duration of time.” Retired U.S. Air Force Brig. Gen. Deborah Rose, a prominent voice for military issues in the Topeka area, became a strong supporter. “I can’t remember when exactly I met her,” Rose said, “but I was very impressed with her ability to grasp the issues at hand, and of course that came from helping her husband when he was so severely wounded and being a patient advocate for him. I’m also a nurse by education, so I understand how important it is for people to have an advocate when they’re either in a hospital or in the health care system.” Jarboe tells a story of a trip to Georgia following a phone call from a military mother whose son suffered severe traumatic brain injury from lack of oxygen while getting his wisdom teeth pulled. Jarboe’s husband had suffered the same type of injury while being treated, and she helped the family push through military red tape and health care restrictions. Ultimately, the soldier’s wife and mother were able to visit their son, which the military hospital had forbidden, and move him to civilian care. “That’s all very confusing if you didn’t know it,” Jarboe said. “And so what I was able to do was get down and listen. I listened to the mother, and then I asked the wife what she wanted, because I wanted to make sure I was within those guidelines. What do you need from me?” While those efforts were rewarding, Jarboe realized she was “no longer serving Jamie” and sought to refocus the organization’s broad mission. A year into existence, the foundation board renamed the organization. MVP’s mission was to honor and empower veterans. But as the organization considered “tightening down what we’re good at doing,” Jarboe said, it looked to traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress. Both afflicted her husband, who served two deployments. He suffered “invisible wounds” before he was shot, Jarboe said, but nobody noticed. “At first I thought it would be really simple,” she said. “Something small. A grassroots movement. But due to our social media outreach and people across the country and then around the world who are familiar with Jamie and me, it ended up growing fast. As an organization, it was hard because we grew way too fast. “Before we knew it, we had a hundred thousand active duty service members, military spouses and veterans register with the Military Veteran Project. Not all of them were requesting assistance, but they wanted to be a part of it. They wanted to make sure they were keeping track of it.” Now, that number is approaching 700,000. MVP board member Steve Ennis said Jarboe’s departure from running operations is a “responsible decision” and “a milestone of sorts for our foundation.” “We need to find the ability to remove some of the administrative responsibilities from her, so she can be more surgical in regard to her investment of time,” Ennis said. “As important as it is to have her be the face, we can’t make the mistake of having her be the only face of MVP.” Jarboe is now caring for four children while investing 40 to 50 hours of volunteer work weekly to MVP. At times, she has used her own funds to bolster events. Although she relishes the organization’s social media breadth - Facebook posts can reach up to 1.6 million people in a few hours - she receives unwanted personal attention and seeks advice from celebrity acquaintances she has met through other military-related foundations. “Stalkers are everywhere,” Jarboe said. “They’re gross. Sometimes, if there’s a picture post of me looking interesting or pretty, they’re all over that. It takes three to five administrators.” She has considered leaving Topeka and went so far as to put her house on the market earlier this year. For the moment, she plans to stay but described her personal life as “one hell of a nightmare.” Securing grant money to hire a full-time operating officer for MVP would help. But she remains cautious of who the organization partners with while upholding her husband’s legacy. “We are still a volunteer-led charity,” Jarboe said. “Our goal is to find the research, complete the research, to help treat traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress to end military suicide. And I think those two things keep me very busy, but then I see the volunteers underneath me working just as hard. “People all over in the nation, right now as we speak, are in one way, shape or form managing a program or campaign that’s reaching veterans, active duty service members and spouses in distress.” Jarboe said she has faced pressure to move MVP to Washington, D.C., or other states where fundraising and networking would be easier. But she is fond of Topeka’s role in launching MVP and praised leaders like Rose and Topeka Police Chief James Brown for their support. Brown said Jarboe “has done much for the veteran community in Kansas” and built “great relationships” with Topeka organizations, including the VA hospital and Topeka Rescue Mission. And her generosity, Brown said, extends to helping honor a Missouri police officer who had been shot during a traffic stop. “Melissa is truly a jewel,” Brown said, “and we are fortunate to have her in our community.” Still, there are times, Jarboe said, when she hopes MVP leaves. “Some people still wonder what we do and how we do it,” Jarboe said. “They just know that we have a large support system. And so I think Topeka has saved us, but it’s also hurt us because it’s such a small community. Most of our donations do not come from the Topeka area.” Ennis said MVP raises about $100,000 per year, and Jarboe said little of it comes from Topeka. But she has used a $50,000 donation from 5-hour Energy and other gifts to help fund Topeka events, including the annual Veterans Day Parade. “Our commitment to Topeka has been very strong over the past three years,” Jarboe said. “We’ve done amazing things here for the local community, the veterans. We work very closely with the veterans administration. They work very close with us, and that’s a great partnership.” For three years, she has organized the Salute Our Heroes Gala in Topeka, initially footing the cost herself. Next year, the event will move to Washington, D.C. The location should make it easier to reach donors, Jarboe said, and Topeka presents logistical challenges for the 30 to 50 wounded warriors who attend. It has been difficult to transport them from airports or find accessible rooms. “Out of ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) places our wounded warriors could go here in Topeka, not everywhere was handicap accessible,” Jarboe said. “That was a hard thing. If they did have the buttons for the wheelchair-accessible ramps, they wouldn’t work or the doors wouldn’t open completely.” In D.C., with support from former Sen. Bob Dole, soldiers will have a presidential honor guard escort them from the airport and an opportunity to tour the White House. But as MVP entertains thoughts of moving the entire organization, Jarboe fears such a change could derail MVP’s commitment to researching traumatic brain injuries (TBI) and post-traumatic stress disorder, and lowering suicide prevention. She is leery of tales about small organizations “created with a passion behind them” that wind up losing momentum after forging dubious bonds. “We’re very cautious,” Jarboe said. “Very cautious about who we want to partner with and who we want to be associated with for our well-being. After all, this is Jamie and my name, so we want to protect that and everything it stands for.” Tens of thousands of service members are diagnosed with TBI each year, the U.S. Department of Defense disclosed in a special report earlier this year. Since 2000, the total surpasses 330,000. Jarboe said 22 veterans, mostly between the ages of 45 and 60, commit suicide every day. MVP is considering a partnership with a major medical institution to research links between suicide, TBI and PTSD. But to do so, MVP would need to raise a lot more money. To get meaningful data, researchers would need to study at least 1,000 patients. Ennis said the cost would be about $9,000 per patient, and they would need $1 million to get started. “That’s a serious undertaking when you consider that would increase our gifts received by almost 1,000 percent,” Ennis said. As with Jarboe, the issue is deeply personal for Ennis. He met Jarboe in high school when she lived in Minnesota for a few years before returning to Kansas. They reconnected on Facebook as she began working to help veterans. “My father was a combat-wounded veteran,” Ennis said. “At the time, when Melissa asked me just to learn more about the Jamie Jarboe Foundation, she didn’t have any idea that my dad was quadriplegic and required a lot of care, similar to her husband.” He has been a board member for the past two years. Like other members, he doesn’t live in Kansas, recently moving from Minnesota to South Dakota. Others live in Minnesota, Indiana, Colorado and North Carolina. Jarboe and Ennis revealed plans to double the size of the board with Topeka or Midwest members who could help choose a leader and simplify goals. Operational growth and expanded fundraising, Ennis said, are necessary and could lead MVP to move to D.C. “It’s scuttlebutt at this point,” Ennis said. “There’s been an idea floated out that maybe we could be gifted some space in D.C. Obviously, if that happened, (it would help) our ability to find other collaborative partnerships.” For Rose, the retired brigadier general and trained nurse, collaboration is Jarboe’s “strong suit.” But Kansas remains a good fit for MVP, she said, because of the “strong military representation” in relation to its size. In addition to Topeka’s Colmery-O’Neil VA Medical Center, MVP is close to Fort Riley, Fort Leavenworth and Wichita’s McConnell Air Force Base. “She’s working with PTSD and traumatic brain injury,” Rose said, “and there are some studies that can be done now that are very specific to help with treatment. The treatment for those two issues is different, but they’ve kind of been lumped together because providers didn’t quite understand what the difference was and how to treat them. And so what her organization is doing is finding resources. “This is something that’s not being done within the VA system.” In 2014, Rose was grand marshal for the Veterans Day Parade in downtown Topeka. “What a wonderful feeling it is,” Rose said. “It’s just exhilarating to me to see all of the spirit for our United States of America and our flag and our military people.” Jarboe initiated efforts to form the parade three years ago. This year, it featured a tank and a skydiver, leaving Jarboe disappointed by lagging attendance. In previous years, the parade was held on the holiday, but she said it was moved to Saturday at the city’s request over safety concerns. Lt. Colleen Stuart said TPD had representation on the parade committee but that the change wasn’t a TPD recommendation. “Discussion revolved around traffic congestion, hindrances to open businesses and overall participation/attendance,” Stuart said. “In fact, it was mentioned that area businesses were upset if the parade were to be held during the open business hours as it would keep customers away.” Organizers estimate attendance dropped to 5,000 people after seeing 8,000 to 12,000 the first two years. “All I know is this was our lowest attendance in the last three years,” Jarboe said, “and that’s very sad.” As a result, the parade’s future is in jeopardy. She called on the community to support the event regardless of when it is held. “They can choose to show up, and they can choose not to,” Jarboe said. “I mean, the parade is for the veterans, but they do rely on the community to help it be successful and move forward. If a certain church can show up every year consistently, then I would think that the regular day civilian can take an hour out of their day to do so, as well.” She noted World War II veterans won’t be around much longer. “They just want to see the community cares,” Jarboe said. “Some of these guys don’t even want the parade, but once they get there it helps them restore humanity and faith that what they fought for, the sacrifices they made, were not in vain.” Ennis traveled to Topeka to attend this year’s gala and parade, getting his first impression of the Kansas capital. “Just from an aesthetic, we came in from the north,” Ennis said. “We saw the old Cargill storage grain buildings down near the river. From the vantage point, it appeared to be a working class city.” He wondered whether Topeka is big enough for an organization grappling with ambition, but he is also sensitive to Jarboe’s concerns. “Well, I mean, it’s home for her, you know?” Ennis said. “As an outside board member, it’s hard for me to comment on it because we’re in this position right now where she’s the pulse of our foundation, and she’s the one that’s operating everything on a day-to-day basis. So could we reach more of the people we need to reach by being in a different location?” Ennis praised Jarboe as “more than full-time invested” and “a driving force for veterans nationwide.” But Jarboe is ready for reinforcements.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Sign up for our mailing list by clicking here

Archives

March 2020

|

|

Get to know us

|

Resources

|

Get Involved

|

|

|

|

|

The Military Veteran Project is a non-profit 501 (c)3 organization, IRS identification number 46-0877378. Donations made to the Military Veteran Project are tax deductible in the U.S. ·

RSS Feed

RSS Feed