The rate of suicide has increased dramatically across most segments of our population in recent years. According to the National Institute of Mental Health, there were more than twice as many suicides in the USA in 2017 as there were homicides. The Military Veteran Project is actively engaged in improving brain health and mental health by providing research and treatment not available or accessible by the VA or DOD to veterans around the world. We are committed to spreading awareness of this distressing issue. Suicides affect many segments of the population, and various factors contribute to this epidemic. Chronic illnesses, both mental and physical, increase suicidal ideation in those who have suffered for years, Military veterans are more likely than the civilian population to develop mental health problems, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and traumatic brain injury. Veterans are also at high risk for developing associated substance-use disorders – all factors associated with suicide. Everyone can play a role in suicide prevention. Major mental illnesses rarely originate “out of the blue,” and oftentimes family, friends, teachers and/or the individuals themselves can learn to recognize small changes before the point of no return. Symptoms listed here, including withdrawal, apathy, social isolation, unusual behaviors, and mood changes, are early warning signs that can be brought to a mental health professional’s attention. Suicides are preventable, and the stigma surrounding mental health problems can and should be addressed in our society. Military traumatic brain injury and its consequences are at a crisis level. There are medical facilities, non-profit organizations and people across the county and around the world that are prepared to unite to fight for the freedoms our veterans deserve when they return home from war, even a simple freedom of proper diagnosis. Since 2012, the Military Veteran Project's small grassroots movement has made huge momentum from Washington DC to Los Angeles to Texas up to Minnesota and even over seas in Europe and the middle east and we know we must continue our efforts. In September each year, our fellow medical facilities and supporters across the country will place 22 white crosses to represent the number of estimated veteran suicides that happen each day. We do not want to forget the sacrifice made by our veterans or their families that left behind. Please join us by simply creating your own "memorial" and alert your local media of the nationwide event. If you are a veteran looking for answers to your questions and need help, please contact us. Click below to join us to help create changeIntroduction

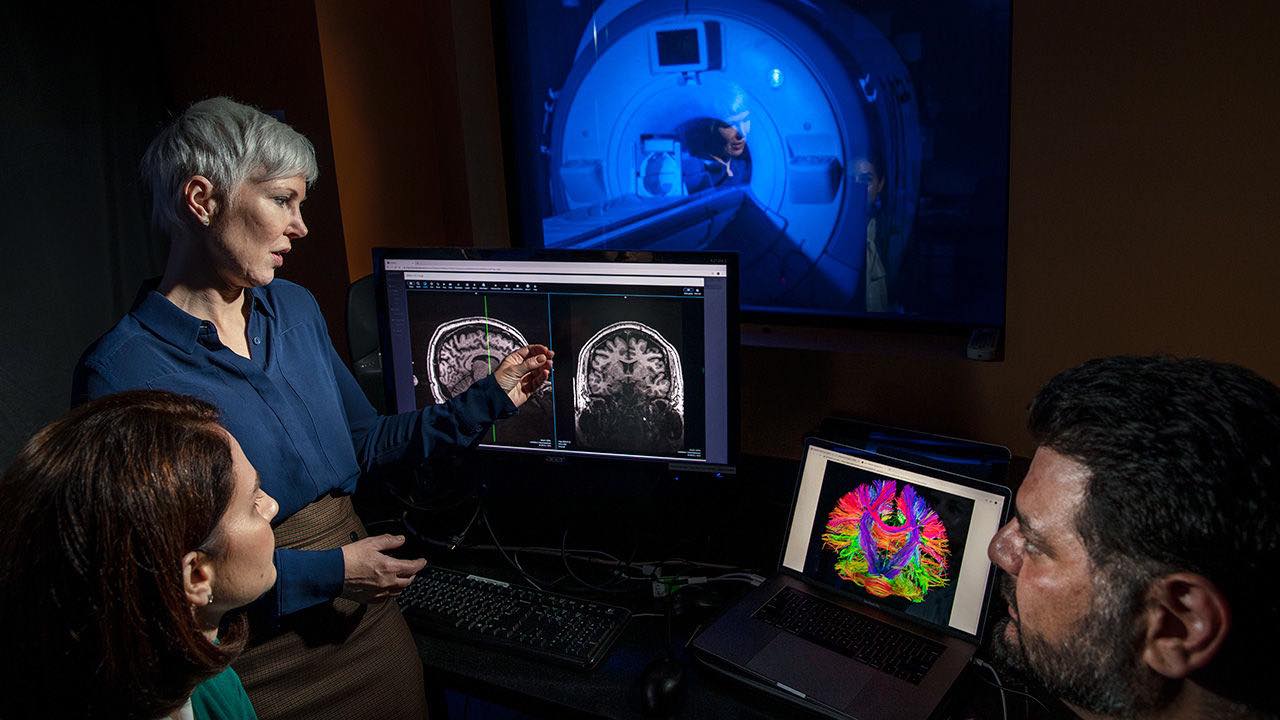

Suicide is a significant public health concern, especially for U.S. military personnel and veterans and has been identified as one of the leading causes of death in the U.S. military (Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center, 2014). Moreover, the suicide rate among U.S. veterans reportedly increased between 2001 and 2014 and risk for suicide in veterans was 21% higher than in the US civilian adults, after considering the differences in age and gender (Office of Suicide Prevention, 2016). Rates of veterans who die by suicide have increased public attention to suicide and underscored the need for research to identify risk factors and to increase suicide prevention efforts in veterans and military personnel (Ramchand et al., 2011; Department of Veterans Affairs, 2013). To date, various interventions ranging from individual to community level approaches are being scrutinized and employed for the prevention and treatment of suicide. However, a limited number of approaches in screening, prevention and treatment have been supported by empirical evidence in part due to the complexity in the psychopathology of suicide in the context of various psychiatric disorders including major depressive disorder (MDD), bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, and substance-related disorders (Klonsky et al., 2016). A stress-diathesis model of suicide behavior proposed by Mann and his colleagues included stressors in the lifetime and vulnerability of individuals as its components (Mann et al., 1999). In essence, when individuals with suicidal diathesis including genetic, epigenetic, and other neurobiological vulnerabilities encountered distress caused by psychiatric disorders and adverse psychosocial events, he or she would be more likely to demonstrate suicide behaviors. Suicide behaviors are defined as self-directed injurious acts with at least some intent to end one's own life (Mann, 2003). Notably, a majority of psychiatric patients do not exhibit suicide behaviors, while >90% of individuals who die by suicide may be diagnosed as having any psychiatric disorders (Bertolote and Fleischmann, 2002; Nordentoft et al., 2011). This observation was consistent with a crucial role of diathesis in the model of suicide behaviors. Moreover, it has been acknowledged that most individuals with suicidal ideation do not attempt suicide (Kessler et al., 1999; ten Have et al., 2009). The critical need for differentiating suicide attempters from suicide ideators has been identified in research on suicide (Klonsky and May, 2014) and investigating the neurobiological diathesis for suicide behavior would address this need. In fact, several structural and functional brain imaging studies on subjects with suicide ideation or history of attempt have been conducted to identify neurobiological differences along the suicide diathesis (Cox Lippard et al., 2014; van Heeringen et al., 2011).

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Sign up for our mailing list by clicking here

Archives

March 2020

|

|

Get to know us

|

Resources

|

Get Involved

|

|

|

|

|

The Military Veteran Project is a non-profit 501 (c)3 organization, IRS identification number 46-0877378. Donations made to the Military Veteran Project are tax deductible in the U.S. ·

RSS Feed

RSS Feed